#Healing doesn’t mean that the #pain goes away. It means that the pain becomes a #sacred part of you that you carry inside #forever. @LoriGottlieb1 https://t.co/DDBWr66dU2 #fightcovid19 #WearAMask #WearAMaskSaveAlife #StayHome #ripTess #ripAtet

— JF 🌊😷 📷 (@JFPerseveranda) February 5, 2021

Grief: "Healing doesn’t mean that the pain goes away. It means that the pain becomes a sacred part of you that you carry inside forever."

PINOY BUILT

February 05, 2021

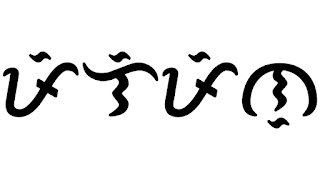

Photo is of Tess and me posing outside of Mindy's Malaybalay in November 1999. We had dinner with her Bukidnon friends and my cousin Michelle.

Found the quote off The Atlantic's Instagram post.

It was a response by Lori Gottlieb in her "Dear Therapist" column in The Atlantic to "Paulina."

I’m so sorry that your father died ,and I can imagine the depth of your sorrow right now. You’re right that it feels profoundly unfair that one day you had a perfectly healthy father, and two weeks later he was dead. And along with him died your vision of the future, which included not just dancing with him at your sister’s wedding and seeing him experience grandparenthood but also decades of silly jokes and warm hugs and the sound of his voice singing those Beatles tunes—a voice that has felt like home for your entire life.

I have no magic words that can erase your pain, but even if I did, I wouldn’t try. That’s because your pain is the result of deep love. It’s your love for your father that creates the pain, and I can’t—nor would I want to—take away your love.

What I can do instead is help guide you through this profound heartbreak—which is, in essence, what grief is—so that instead of “accepting” your father’s death, you begin to accept your feelings in all their wild glory: the rage, the guilt, the sadness, the despair, the envy of people whose parents survived COVID-19 while yours did not. Because when you accept these feelings, fully and without judgment, you will slowly begin to heal.

Healing doesn’t mean that the pain goes away. It means that the pain becomes a sacred part of you that you carry inside forever. Often grieving people come to me hoping I can help them find “closure,” but I’ve always felt that closure was an illusion. Many people don’t know that Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s familiar stages of grieving—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance—were conceived in the context of terminally ill patients learning to accept their own death. It’s one thing to “accept” the end of your own life, but for those who keep on living, the idea that they should be getting to acceptance, or what we think of as closure, might make them feel worse (“Why am I not ‘over this’ by now?”).

Besides, how can there be an end point to love and loss? Do we even want there to be? The price of loving so deeply is feeling so deeply—but it’s also a gift, the gift of being alive. If we no longer feel, maybe we should be grieving our own death. The grief psychologist William Worden takes into account this perspective by replacing Kübler-Ross’s stages with tasks of mourning. In his fourth task, the goal is to integrate the loss into your life and create an ongoing connection with the person who died while also finding a way to continue living.

Right now, though, the pain of your father’s death feels unbearable. A patient once told me that her grief made her feel “alternately numb and in excruciating pain.” Yours may feel like that or it may feel different. You might also experience a sense of surreality: How can people go on with their days as if nothing has happened? How can they binge-watch TV shows and share gingerbread-cookie photos on Instagram when the world seems to have stopped? And comparing your loss with others’ is natural, too: Is it worse if the death is sudden or expected? If the person is 62 or 80? If you saw the person regularly or hadn’t seen him in a year? But grieving is not a contest, because there are no winners when it comes to losing someone you love.

Still, while there’s no hierarchy of grief, the coronavirus has made the grieving process more complicated because the rituals that normally support human sorrow—being at a loved one’s bedside, saying goodbye, viewing the body, having a funeral, getting hugs and meals and sitting in the same room with people who care about us—have been taken away. And then there’s the experience of being constantly surrounded by COVID-19: seeing people wearing masks every time you go to the supermarket, hearing reports of more deaths on the news every day. These reminders can be retraumatizing, as if your loved one had died in an automobile accident and all you saw every day were endless images of car crashes.

So what can you do in the face of your loss amid these extra challenges? You can be kind to yourself and practice self-compassion. You can embrace the rage—because it’s valid. You can disinvite the guilt when it attempts to pay you a visit by reminding yourself that there’s nothing you could have done differently. (It wasn’t safe for you to travel. You didn’t know your father would get the coronavirus. Your father knew how much you loved him, even if the devastated part of you might suggest you believe otherwise.) And you can bear in mind the concept of impermanence. Sometimes in their pain, people believe that the agony will last forever. But feelings are more like weather systems—they blow in and they blow out. Just because you feel gutted this hour or this day doesn’t mean you’ll feel that way this afternoon or next week. Everything you feel—anxiety, anguish, joy—blows in and out again. There will always be pain. Hearing a Beatles song on the radio might even plunge you into momentary despair. But another song, or another memory, might bring intense joy minutes or hours later.

So when you do fall into self-blame, rumination over how things might have gone differently, and protesting the death itself—all of which are ways to not experience the more tender feelings of sadness and loss—be gentle with yourself. Get sleep, eat well, move your body, go outside, find emotional respite by engaging in hobbies you enjoy or watching a movie. Connect with others over Zoom, and create rituals to memorialize your father such as sharing memories or photos with friends and family, which you might even compile into something tangible, like a book or album or video.

There is no way around your grief, but there is a way to move through your pain. Be patient with yourself. Try to remember that eventually you will come to view the world as neither all good nor all bad. Hold a space for the fact that you hurt so deeply because you were loved so deeply. And let that braid of pain and love be a reminder that you are human, and you’re exactly where you need to be.

Posted by: PINOY BUILT

Founder, Social Media Manager & Content Creator at Pinoybuilt.com. Photographer. Former IT Product Manager at Pacific Gas & Electric. I'm a 1.5 generation immigrant—Filipino-born, U.S.-raised—sharing stories that bridge cultures. Share yours at PINOYBUILT.com. I’m still learning about our roots, and I invite you to learn with me. I was born in Makati City and raised in Marikina, known for world-class shoes and strong community ties. I went to Marist School; my sister went to St. Scholastica’s. We spent weekends in Malate—those memories of old Manila still shape who I am. At 9, we moved to Chicago, where I saw snow for the first time. At 12, we relocated to Vallejo, CA. Since then, I’ve lived in Davis,Glendale (SoCal), back to Chicago in my 20s, San Francisco & Fremont. I visit SoCal often for family. Chicago will always be special—but go Golden State Warriors! At UC Davis, I was a member of Mga Kapatid, where I had the chance to participate in Pilipino Culture Night and perform traditional dances like Bangko. Now, as a father of three, I’m doing my best to pass on our Filipino heritage. Let’s build something Filipino together. Mabuhay.RECENT COMMENTS

Followers

Total Pageviews

Trending Last 7 Days

Happy New Year everyone!

January 01, 2013

Diana's Birthday Party: Maligayang Bati

December 27, 2012

The Story of Filipino Martial Arts in Stockton California

January 31, 2020

Happy 11th birthday to our favorite son/brother!

January 14, 2013

Lolo Marciano on USS Midway

February 04, 2021

Watch: Janine Tugonon featured in Victoria's Secret ad

September 14, 2016

Suspended nurses in CA decry lack of protective equipment

April 22, 2020

LINKS

Popular Last 30 Days

Inauguration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

June 29, 2022

Hiddenbrooke Swimming Pool

June 02, 2013

Happy New Year everyone!

January 01, 2013

Popular Alltime

Das Festhaus - Williamsburg, Virginia

November 05, 2024

Jollibee: Virginia Beach 4541 S Plaza Trail Drive

November 23, 2024

Janine Tugonon wins Nu Muses competition

October 02, 2016

Menu Footer Widget

Copyright ©

VIRGINIA FILIPINO AMERICAN

0 Comments